Interview with Catherine Abbey Hodges – First Friday Open Mic at Dagny’s, May 2, 2025.

By: Carla Joy Martin

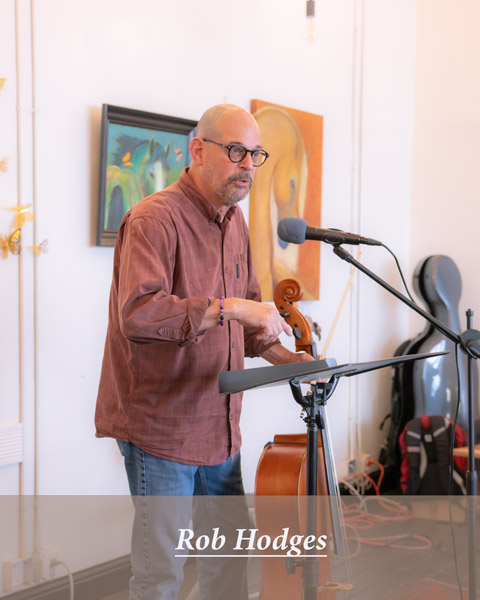

Catherine Abbey Hodges performed her exquisite poetry for us, accompanied by her husband, Rob Hodges, on cello. Listeners were blessed by the melodic interplay between Catherine’s imagery and Rob’s improvisational music.

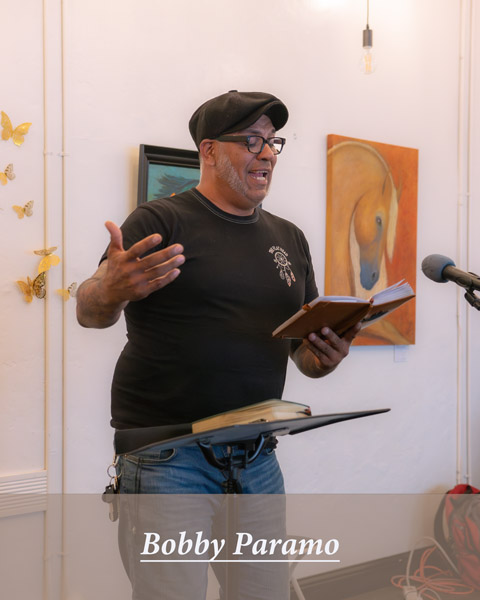

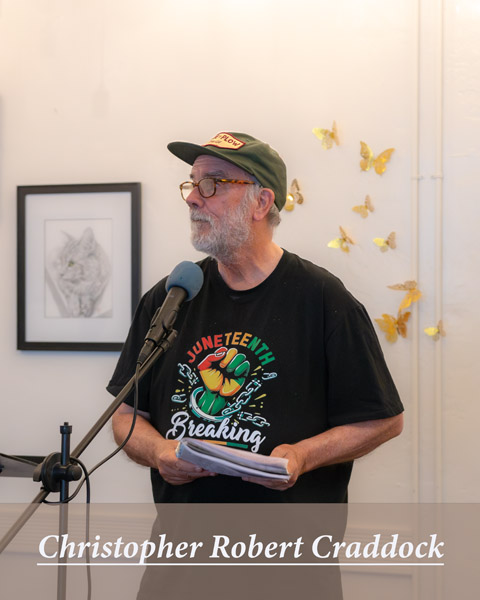

Other participants in the evening’s Open Mic were:

Q. When did you start writing poetry? Was there an event in your life or inspiration gained that led you to write in this genre? Are there any poets that have influenced you? Who have messages you connect with, or styles you admire?

A. My parents loved reading. Before I could read, they read to me, and once I was able to read for myself, my nose was always in a book. It was a perfect fit for a shy child, and the natural corollary was that as soon as I learned to write, I started writing stories and keeping notes on my thoughts. That said, though I had loved poetry for years, I didn’t start writing poems myself until I was almost 40, when I had things to say and questions to explore that I couldn’t approach any other way.

There are so many poets whose work I love and am indebted to. To name a few, I recognize the influences of Annie Dillard, Wislawa Szymborska, Stanley Kunitz, Seamus Heaney, Peter Everwine, Marie Howe, Thomas Merton, and Jane Hirshfield on my poems.

Q. You are a master of enjambment and poetic form on the page! How do you decide what form your poem should take? Whether to use couplets or other length of stanzas? Perhaps you might explain what enjambment is for our readers – and how it enhances a poem?

A. You’re very generous, Carla Joy. I find form endlessly fascinating. I like to think of forms as containers into which we can pour our drafts. For example, if I have a long, skinny first draft, what will happen if I pour it into a sonnet form of 14 lines? Or into couplets (two-line stanzas) of long lines? How do these alternative forms shift the emphases of the poem? Very practically speaking, it helps me to keep a single document of a poem-in-progress, cutting and pasting so that each new version adds to the document. That way I can keep track of the progression of drafts, and I’ll often return to a draft that’s somewhere between the first and tenth and recognize it as the one I want to keep working on.

You asked about enjambment, which refers to a line of poetry that ends before the thought ends. It’s the opposite of an end-stopped line, where a line ends with a period or at least a complete thought. This is another thing to experiment with in drafts: how is the meaning of your poem changed if the word you end a line on suggests a variety of options for how the thought might end? For instance, if a line reads,

“After that, he lost”

imagine what could come in the next line: “his wallet,” “the game,” “his mind,” “his brother,” “everything” . . . –the reader pauses at the end of the line in a momentary consideration of possibilities, and the poem may be enriched by this. On the other hand, a plain-spoken poem with mostly end-stopped lines has its own kind of power. Sometimes when we love a poem, it has drawn us in through its combination of end-stopped and enjambed lines.

Q. When did you and Rob start to combine your talents and perform together? How does his cello music enhance your verse? Do you rehearse ahead of time, or just wing it and improvise in the moment?

A. Rob and I started performing together when my first book, Instead of Sadness, came out in 2015. It struck us as a rewarding way to collaborate, and we’ve been doing it ever since. Our hope is that the cello responses offer a kind of sonic space for listeners to bring their own thoughts to the exchange of words, silence, and sound. As for how we prepare, I plan the poems I’ll read, and their order, in advance, and share the list with Rob. That’s it for preparation (well, except for his 55 previous years of playing the cello!)—no rehearsal. We like to see what will emerge. He’s very improvisatory.

Q. What advice would you give to other folks wanting to create poems? How do you make a poem? Do you have a special place you go to, or music you listen to, etc.? Do you write on a schedule, or do you wait for inspiration? Give us a glimpse into your creative process.

A. I write every day—good old journal entries, nothing fancy—as a way to think about my life, my relationships, events in the world, memories, and so forth. As I’m writing, when an image or a phrase comes up that I think might lend itself to a poem, I put an “X” next to it in the margin, and another at the top of the page. That way I’m creating my own sourcebook, and I work from these notes to start poems. I also read a lot of poems, and I study the ones I love in order to learn their moves. The poems of others are a poet’s best teachers.

For those who’d like to start writing poems, I’d say: just start. You might start with “There should be a word for . . .” and keep writing, see what comes up. Another good start: “I used to think _______________, but now I think . . . . .” Or take a news headline and start there. I have a poem based on an article titled “German Scientists Discover Water Has Memory”—my poem is called “What Water Remembers,” and I had a wonderful time imagining what I might remember if I were water. It turned out to be a poem about climate change, though I arrived there unintentionally. That’s one of the great joys of poetry: the surprise of where it will take you.

Here are the last two poems I read at Dagny’s in early May, both from Empty Me Full (Gunpowder Press, 2024).

BLOOM AND BLOOM

Here I’d assumed one poem about jacaranda blossoms

underfoot would be my lifetime quota. But that misses

the point, since I know I won’t know till I’m well in

or done what the thing is about, that filament, shred

of incandescence, essence

to which, if anything can get close, it will be a poem feeling its way,

talking to itself between silences.

(stanza break)

I’m here for that, or in the next room, ear to the wall. Spendthrift

world, it’s me again, listening hard,

talking you up, extolling your gullies and beetles, your bruised

blossoms on the pavement, the ones that bloom

and bloom even once they’re dust.

OLD BLUE SHIRT

A time zone away, someone I love

is taking a test. For him, I’ve tried

to hold myself still for a square inch

of time. It’s the least I can do

and the most, something like prayer,

but less wordy. This is the boy who saw

an angel down a dim hallway at dawn.

Years later, another in the Grand

Canyon: mineral visitor, feathered flood

and flame. Something passed between

them, I think, though I didn’t want to pry.

I haven’t seen an angel, but I’ve taken

years of tests, lately of my vision,

my platelets, my capacity for stillness.

Oh wait a minute. Could the bird

that sang sweetie sweetie sweetie

a moment ago really be singing stupid

stupid stupid now to the same tune?

In my mind a table. On it, the usual

mess, sweet and stupid, stupid and sweet,

and me in my old blue shirt, in a chair

from a long-gone kitchen, looking

out the window at myself looking in,

and both of us thinking: how did we

get here? And can we stay forever?